Satire or smear? Islam-themed cartoons

This is a guest post by Sarah AB

Recently the Online Hate Prevention

Institute (OHPI), which is based in Australia, published an interesting report

on anti-Muslim bigotry within social media – you can download it here. The author, Andre Oboler, has also published

on antisemitism. He and I have rather

different perspectives on free speech issues – I'm wary of bans and censorship, whereas he’d like to see some tightening up of the law on

hate speech. I do not agree with the

recommendation he makes on p. 7 of his report:

The Australian Government should pass laws to make vilification on the grounds of religious belief or practise unlawful and expand the remit of the Australian Human Rights Commission accordingly.

Criticism of anti-Muslim discourse is

associated in many people’s minds with a threat to freedom of speech. This is not unreasonable, given the murderous

attacks on some critics and satirists of Islam, and the existence of illiberal

and repressive blasphemy laws which have had a particularly chilling impact on

dissident Muslim voices. So I’ll begin my stating that I certainly don’t want

to ban any of the examples I refer to

in this post, just to explore whether they are bigoted or whether they are

making legitimate, even important, points.

A number of posters and cartoons were

reproduced in the report. People concerned

about free speech (rightly) assert that satirical criticism of Islam, or

aspects of Islam, need not be bigoted.

But some of the material highlighted by Andre Oboler helps demonstrates that this can be a difficult border to police.

On page 14 of the report you can see a poster with the text:

The cult of Islam has no intention of fitting in. Muslims will never become part of a civilised society.

Another example (p. 18) is a poster

depicting a nuclear fireball and the caption:

Some cancers need to be treated with radiation: Islam is one of them.

It would be possible to argue that the

second poster only criticizes an idea – that it targets Islam, not Muslims. But

there’s an uncomfortable slippage here between the literal and the

metaphorical, particularly if you have come across calls to bomb Mecca.

A very straightforward example of

dehumanizing anti-Muslim rhetoric can be found on p.17 where a plane, labeled

‘humans’, is carrying a crate labeled ‘Muslims’. There are valid reasons to avoid the term

‘Islamophobia’ – but surely any reasonable person would agree that cartoon is

bigoted.

So – what satirical treatment of

Islam/Muslims is not bigoted? Both

the Tell MAMA working definition of anti-Muslim prejudice and the EUMC working

definition of antisemitism (I compared them here)

emphasise the importance of context. When

trying to answer my own question, I often found myself wondering who produced a

particular cartoon, for whom, and why.

Although it would be absurd to require that

every satire on something Islamic comes accompanied by the kind of ultra cautious

remarks which preface this clip, a climate of anti-Muslim bigotry may make

people look more closely at the context/provenance of Muslim-themed

satire. I think that’s why there has

been some slightly anxious speculation as to whether Twitter’s favourite parody

Sheikh, King of Dawah, is at least culturally Muslim.

Content as well as context, of course, also

helps one determine whether bigotry lies behind satire. Depicting the victim or antagonist of Muslim

extremists as a Muslim

creates a completely different effect from images which

project a ‘Clash of Civilisations’ subtext, as in cartoon B26 of OHPI’s report

(p.70), a blonde woman kicking a Muslim pig off the map of Europe. But a complication may arise for the viewer deciding how to respond to images featuring Muslim women.

I believe I came across both these images

on rather dubious sites. But many Muslim and ex-Muslim women (and

their male and non-Muslim allies) bitterly resent those who insist that this

kind of dress is desirable, even mandatory, for women. Whereas this ‘joke’ about binbags seems

dehumanizing I’d hesitate to criticise the paper doll image, which presents the woman in a

non-stereotyped way, and could certainly be seen as a legitimate satire on

theocratic dress codes.

The same uncertain borderline between legitimate

criticism and racist bigotry is a problem within discussions of antisemitism. Recent examples by Steve Bell and Gerald

Scarfe have generated much debate. Latuff is often accused (quite rightly in my

opinion) of allowing criticism of Israel to be tainted by antisemitism – the

use of Nazi imagery is a common problem in his work. But here is an example which,

for a change, doesn’t seem too problematic.

Returning to Islam – a recent example of

censorship caused widespread indignation.

This was when atheist students were forced to cover up T shirts bearing

this image. I’m a great fan of Jesus and Mo, and I supported

those students. But perhaps taken out of

context that particular cartoon could make people think it was a reflection of

bigotry against Muslims, not just satire against religion. There is a reference to burning things – that

could be seen as a comment on (Muslim) over-reaction to ‘offensive’ material,

rather than, as is more clearly the case with this earlier Jesus and Mo, a satirical

observation on religion.

Both the EUMC WD and the Tell MAMA

definition emphasise the importance of context, and Tell MAMA specifically

identifies an individual’s track record as a factor which should be taken into consideration when making a judgement. When looking up cartoons about

Islam, I found much that was aggressive and unfunny. But Jesus and Mo is

neither, and, taking that wider context into full account, the T shirt that was

banned from the LSE strikes me, not as incitement to hatred or bigotry, but as

a legitimate comment on attempts to silence satire – softened by the resonances

of the Jesus and Mo ‘brand’ which is so different from the images you will find

on some counterjihad sites. See for example image D20 on page 89. And shouldn’t one be able to use satire to

show contempt for those who want to curtail freedoms with violence, whether

or not they act in the name of Islam? As

I mentioned at the beginning of the post, it’s Muslims who bear the brunt of

blasphemy taboos.

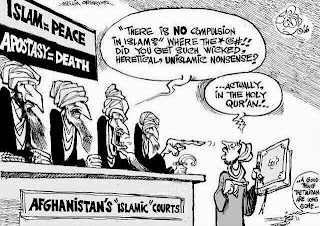

Of course Jesus and Mo isn’t in the

report. But B24 (p. 69) is – should it

be? It depicts a Muslim wearing a metaphorical suicide belt of

‘multiculturalism’ while anxious onlookers tiptoe around his supposed

sensitivities. Andre Oboler offers no analysis of this. I can understand why an image of a rather

sinister looking Muslim deceiving non-Muslims might cause concern. But, again, the underlying message of the

cartoon is not something anyone who, for example, opposed Ken Livingstone’s

embrace of Qaradawi, or is pleased Hope not Hate is tackling Muslim extremists

as well as the traditional far right, can easily distance themselves from.

Comments

People seem to have a very hard time understanding the qualification you make at the beginning: that saying you find something offensive or racist does not mean you want it banned. We need to keep ramming this point home: that defending free speech does not mean saying the message is acceptable, and conversely that criticising racism does not mean stopping free expression.

Probably my only difference of emphasis from you would be to put less stress on the authorship of these sorts of images in thinking about "context", and putting more stress on the continuities with pre-existing discourse and on effects. In terms of authorship, this is especially true in our viral age, when a cartoon or other image so rapidly moves out of the context of its production into other contexts: a non-antisemitic anti-Israel cartoon by Latuff might be innocently retweeted by a non-racist Israel-critic, and that'd be fine; conversely, a completely non-offensive cartoon about Israel or Islam reproduced by a fascist site among a bunch of offensive ones can become not so fine.

In terms of discourse, I think the issue with the Scarfe cartoon, for example (which I thought was not offensive), was that it was taken by some to play with blood libel imagery. In the case of Islam, certain images are part of a repertoire of anti-Muslim racism, and playing with them in a non-racist way might risk perpetuating these images (I can't think of a good example of that).

And in terms of effect, I think that the hurt caused by an image, regardless of its intent, does matter, even if it is not sufficient in making a judgement. What's interesting about the LSE Jesus & Mo ban is that noone seems to have actually complained; the university _assumed_ people would be offended.

The problem with the word " acceptable " is that it immediately raises the question... acceptable to whom ? And this in turn immediately raises the question does anyone, and if so whom, care whether it is acceptable to these people that find it unacceptable.

But although images can and do become 'contaminated' by the company they keep I think it's important that the far right (and anxious liberals) don't make it impossible for dissenting Muslims/anti-racist secularists to make use of sharp satire.

I also thought that the Scarfe cartoon was ok - but for me that was a matter of first seeing a very strong prima facie case against it which was softened by learning/thinking more about context - authorship and intention.

http://zionistsbehavingbadly.wordpress.com/2013/12/12/proper-people-not-girls/

But it assumes that multiculturalism is a problem caused by Muslims and experienced by non-Muslims when that is in fact a false divide. Some non-Muslims are responsible for the worst effects of (versions of) multiculturalism and many Muslims suffer because it is assumed they don't value the same human rights non Muslims do.

And personifying political multiculturalism as a terrorist reinforces the Islam/terrorism link which is in fact rather distracting if one's real target is multiculturalism as many people who support a multiculturalist agenda and/or highly illiberal ideas will sincerely denounce terrorism.