How would you like it if I called you bilingual?

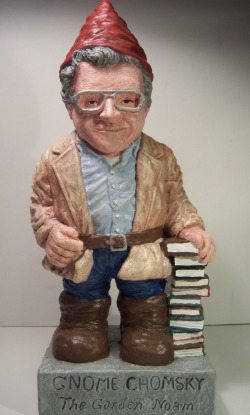

After my tussle with Gabriel Ash over Chomsky's genocide denialism, after Martin posted some fantastic Gnome Chomskies, after revelations of Chomsky's capitalist business practices, after Venezualan anarchists have described Uncle Noam as "Chavez's clown"... I felt it was time for a Noam Chomsky post. However, not having the time to write it, let's hand over to Ali G.

After my tussle with Gabriel Ash over Chomsky's genocide denialism, after Martin posted some fantastic Gnome Chomskies, after revelations of Chomsky's capitalist business practices, after Venezualan anarchists have described Uncle Noam as "Chavez's clown"... I felt it was time for a Noam Chomsky post. However, not having the time to write it, let's hand over to Ali G.Just before I do (because it is related), can I recommend Michael Tomasky's take-down of Michael Moore as a "blowhard"? I got there via Martin's post on the "anti-imperialist reflex" of the "post-left" (that also applies to Chomsky). Another person taking apart the anti-imperialist left, or "Manichean left" as he calls it (and he includes Chomsky), is Michael Bérubé in his new The Left At War - read a free sample here and a review here. Angilee Shah sums up:

Bérubé pits Noam Chomsky against Stuart Hall; the divide lies between what Bérubé calls the “Manichean left,” which did not just oppose the Iraq war but supported resistance to America’s intervention, and the “democratic left,” which maintains that, though U.S. foreign policy is not always guided by virtue, there is still space for the defense of human rights in the international sphere. To put it another way, one side of the left adopted the position that state sovereignty is supreme and another said that the world has a responsibility to protect repressed people. These seemingly irreconcilable principles — both which have become hallmarks of leftist thinking — collided on 9/11. “The left suffered for decades because one branch of the family tree was willing to tolerate a certain degree of tyranny if it advanced the material well-being of the peasants or proletariat,” Bérubé writes. “The left does not now need another branch whose position on tyranny is that tyranny is bad, but tyrants can only be legitimately overthrown by their victims.”And, finally, Scott McLemee has slaughtered another sacred cow of the post-left, Brother Cornel West. He also responds to his critics here.With a Democrat in the office, about to increase troop levels in Afghanistan, this argument leaves the left in an awkward position. Can those on the left support Obama’s position even though Chomsky predicted that the war in Afghanistan would become a “silent genocide”? Bérubé is ultimately optimistic that a middle ground can be found in a “democratic-socialist, internationalist left” that encourages “a capitalism with a human face,” and insists on human rights at home and abroad.

So, here we are. Ali G interviews Noam Chomsky, humourless ponce.

Oh, for the sake of fairness, here are two defences of Chomsky, from Slack Andy and from Phil Dickens.

Comments

Anyone mystified by Andrew's reference, incidentally, should consult this.

http://www.youtube.com/user/VaSavoir2007#p/a/u/0/vD8Eghw1Bik

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.com/2009/12/broadcasting-standards-authoritys.html

Merry Xmas 'n all

When he's right he's very right. But he fucks up a lot.

I think a lot of it is that Chomsky is incredibly prone (and this sees to be getting worse as he gets older) to having attacks of liberalism. While this analogy is liable to cause shrillness if repeated to the usual suspects, Chomsky's support for Chavez comes from the same place as his call to "hold your nose and vote Democrat". Whenever a clear class analysis is called for, Chomsky is invariably found wanting.

That's what leads to the genocide denial and the link up with reactionary groupings that Mod outlines. Anti-imperalism is, at its core, a particular strand of liberal analysis. In Chomsky's case, he's taken the "criticise your own state first" argument a step further and starts from an position of support for any group fighting US capitalist interests. Which leads him not to do his reseach properly and hence he ends up as an apologist for genocide.

Then combine that with the fact he's incredibly reluctant to admit it when he's wrong. I don't think that's peculiar to Chomsky, or even leftist academics. It seems to me to be a very common trait among academics generally. It's why academics are a bit of a mixed blessing for political movements, they tend too heavily towards treating the world as if it was one of their students. And groups that mainly consist of academics are at best irrelevant. That's a particular problem on the left because, with a handful of exceptions, academics are isolated from wider social movements and are actually pretty ignorant about the facts on the ground. So they prioritise abstract theorising over praxis and/or see the campus as the main arena of struggle and political debate. It very rarely is.

On the other hand, anyone who calls for "a capitalism with a human face,” is not in any way part of the left, whatever they claim to the contrary. Bigger cages. Longer chains.

http://contentious-centrist.blogspot.com/2009/12/garden-noam-garden-variety-gnome.html

To the best of my knowledge, Chomsky has never called himself an anarchist. He may be an anarcho-fellow-traveler but that's about it. I even remember reading an interview where he was asked "are you an anarchist?" and he replied "no." I'll try to find a link.

A lot of people think the historian Paul Avrich (RIP) was an anarchist as well. I remember hearing him speak at the Queens Public Library and a young activist asked him if he was. He paused and said he had a great deal of respect and admiration for the anarchists he has interviewed over the years (for "Anarchist Voices" and other works) but that he did not have the level of political commitment and dedication to consider himself an anarchist.

Thanks for that. It sounds like we're in the even stranger position of the most prominent media 'anarchist' not considering himself an anarchist!

I'm not sure he's even an anarcho fellow traveller as such. While there's obviously some points of agreement and common interest, there's an equal amount of differences, his support for state power and in particular. It's interesting to me if we compare him to someone like Murray Bookchin, who didn't consider himself an anarchist at the end of his life, but there were still a lot of similarities between his politics and anarcho-communism.

I suspect Chomsky's attracted to anarchism as an abstract philosophy, but not as an actual political movement.

The first point is that the review suggests he mixes up "liberal" with "radical left". While that's very common in current US discourse, it's unforgivable for an academic writing a book on politics.

Next, what precisely does he mean by "Manichean left"? I genuinely don't know. If you're going to use new terms, fair enough, but they need explanation. The two most likely interpretations (based on the etymology of the term) are both problematic. If he's using it as a way of saying 'dualistic', that would be somewhat ironic considering how binary his perspective on the left actually is. If he's using it to mean that the left refuse to accept that there is a completely benevolent force for good (how the term was used most commonly in the Middle Ages), that's even more laughable. Is he suggesting the interests of the US government are entirely altruistic? Of course, he might mean neither of these things. But that's the problem you get when you start talking in postmodernist jargon. I suspect he may have trouble getting out of the mindset of being a cultural studies lecturer. (Ooo, cheap shot!)

To put it another way, one side of the left adopted the position that state sovereignty is supreme and another said that the world has a responsibility to protect repressed people.

I really hope that's a bastardisation of his arguments by the reviewer. Because, if not, he's using straw men. And not particuarly subtle ones.

Even the most one dimensional of the anti-imps aren't making an argument based on national sovereignty. If anything, that particular argument is far more common on the isolationist right. It might be an easier argument to throw out, but even a vague knowledge of the far left should be enough to suggest that it's not the case. (Are we expected to believe that Trots seriously make this argument, despite the their theoretical being international revolution? Just how stupid doesBérubé think we are?)

On the flipside, arguing for the protection of repressed people is much like arguing for 'freedom'. It's vague enough that nobody is going to seriously disagree with it. What matters is the details. How is he defining 'repressed'? How he he proposing we protect them? (Does he support military action against China to protect the Tibetans? If not, why not?) Does he have a practical suggestion for what the left should do, or does he see the role of the left as passive spectators to state action? How does he reconcile that with the recognition that "U.S. foreign policy is not always guided by virtue"? All of these are vital questions and ones where the decents are sorely lacking in answers.

The left suffered for decades because one branch of the family tree was willing to tolerate a certain degree of tyranny if it advanced the material well-being of the peasants or proletariat,”

Sure. But neither do we need those who refuse to fight for economic democracy as well as political. Who replace the fight for liberation with some vague conception of 'human rights'. Who are prepared to support a certain degree of poverty as long as the 'rule of law' is maintained. Who think we should find a middle ground between socialism and barbarism. (Barbarism with a human face perhaps?)

For the sake of argument, let's ignore the capitalism red in tooth and claw that was in place under Pinochet and that exists in sweatshops. Let's just look at the 'human capitalism' that exists in the west. It still kills. Directly (homlessness, poverty, lack of basic heating over winter) and indirectly (check out the differences in life expectancy according to class). So there's a darkly humorous irony that this quote is from a post that also looks at a case of genocide denial. The parallel isn't quite exact. Genocide is obviously a systematic, deliberate act. Whereas capitalism kills as a necessary byproduct of its existence. So Bérubé is more like a Maoist who completely refuses to acknowledge the deaths caused by the Great Leap Forward.

As for the idea we should have a "democratic-socialist" left that encourages capitalism, I think Orwell says all that needs to be said.

I am well aware that it is now the fashion to deny that Socialism has anything to do with equality. In every country in the world a huge tribe of party-hacks and sleek little professors are busy 'proving' that Socialism means no more than a planned state-capitalism with the

grab-motive left intact. But fortunately there also exists a vision of Socialism quite different from this. The thing that attracts ordinary men to Socialism and makes them willing to risk their skins for it, the 'mystique' of Socialism, is the idea of equality; to the vast majority of people Socialism means a classless society, or it means nothing at all.

A couple of more general observations about the decent left, not directly related to the review.

The main countries that the decents look at currently are Iraq and Afghanistan. (Understandably). I think it's fair to see that it's too early for either me or them to argue that our viewpoint has been proven to be correct by events there. What I would say however is that it is a matter of undisputed fact that western individuals, governments and companies were involved in providing support to reactionary forces in both countries, the same groups that decents claim to see as fascist and in many cases the same ones we later went to war with. Now, that doesn't negate the decent call for action now. However, many of the people who backed those groups are known to us. Where is the call for action against those people from the decents? Why aren't they calling for Donald Rumsfeld to be charged with aiding and abetting genocide? Why aren't they supporting and participating in direct action against arms dealers? It's the moral relativism they claim to be against. It says that we shouldn't take action against those responsible for genocide if they're rich westerners. There is no other logical explanation for this I can think of.

I have no particular love for the idealised 'worker' as he appears in the bourgeois Communist's mind, but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.

And he certainly does describe what he means by the Manichean Left. A reason for the term is that he doesn't want to concede ground to those who think they're "leftier." For some, it can work out that to declare the sky to be blue is to declare your allegiance to mainstream, bourgeois values. To rebuke them as "far leftists" or in a variety of other ways doesn't work because they take that as a compliment. Further to the left, for them, means further to the correct, even if it goes off a cliff. So Bérubé deals specifically with a Manichean tendency that underlies at least some of the more significant mistakes. At the same time, he doesn't want to get into claiming the authority to declare a proper way to be a leftist, because that's a useless argument that diverts discussion from what's correct to what's left.

Where I think you might have difficulty with him is his debt to Hall and Richard Rorty and, generally, to cultural studies. He writes at some length of a gramscian notion of hegemony which is not strictly top-down, in which ordinary people participate. I suspect you might be willing to struggle through that, but I suspect even more, that you might get something out of it. I don't think he's perfect, but he's much better than simply "worth tackling."

1. On Chomsky the celebrity "anarchist". I think that he is a celeb because he expresses a simplistic narrative in a very authoritative, persuasive, articulate way. The simplistic narrative may have a simple truth at its heart: about the nature of power in a capitalist world. But it is simplistic because it airbrushes out any nuances that blur that picture. And his authoritative expression is partly a matter of his status as a linguistics genius and his apparent but sometimes dishonest use of academic rigour, or, rather, of the rhetorical trappings of academic rigour. More on this in a later post.

2. On Chomsky's "liberalism". Part of what is wrong with Chomsky is his liberalism, one of the points I made in my What's Wrong With Chomsky post a while back. But in some ways, I share some of the "liberal" attributes WS criticises here: holding my nose and supporting lesser evils, in the lack of faith in the achievement of the better good soon enough - a bird in the hand rather than the bush.

3. On Chomsky and Avrich as not anarchists. I know Chomsky identifies as a "libertarian socialist" (as did Bookchin), but I thought he saw that and anarchism as essentially the same (unlike the late Bookchin). His Wikipedia page claims he is an anarchist, citing the AK book Chomsky and Anarchism. He wrote the preface to Daniel Guerin's sympathetic history of anarchism (Guerin was also not an anarchist but a libertarian socialist) and to one of Rudolf Rocker's books.

Avrich has a lot in common with the British historian of anarchism Bill Fishman, a lifelong democratic socialist and Labourite. Fishman's book East End Jewish Radicals was extremely influential on the 1970s revival of anarchism in the UK (as Avrich's work was in the US) but he gave a particular spin to his hero, Rudolf Rocker. (Vic Seidler, a veteran of Big Flame and Solidarity gave a very good account of this at a Rocker centenary event at Toynbee Hall a year ago, saying that Fishman's version of Rocker gave them the tools to develop a libertarian socialism relevant to the day to day struggles of the East End in the 1970s. Thus, for example, Fishman emphasised Rocker's critique of orthodox Marxism and its iron laws of history, his related critique of the doctrine of revolutionary purity (Rocker believed that bread today is always more important than jam tomorrow), his critique of voluntarist shortcuts like terrorism. Rocker, of course, was a big influence on Chomsky, and some of the aspects of Chomsky’s “liberalism” that WS dislikes are also elements of Rocker’s anarchism. (Rocker saw anarchism as descending from both the liberal and socialist traditions.)

I have a pet and somewhat trite theory about the Left post 1914. The shock, total and blinding, of the 2I due to the popular leap into total war seemed to splinter the leftist imagining and set of 19th century sensibilities in half. There was always the tension there, but 1914 and the then constant 'absence of peace' ripped out any capacity for reconciliation.

Both fragments had to evolve both to calamitous and unthought of changes and in denial of what they shared, their common ancestery. Thus the 'no, i'm a REAL socialist' games.

The Ebertists, for want of a better phase, hyper-ventilated the Jaures dilemmia, when to support a 'actually existing' repressive state over an assumed greater evil. In the case of Ebert, the tiny possibility of a full Bolshevik style take over and thus civil war. The SDP leadership decided killing comrades, ball cupping a culture of insidious nationalist terrorism and protecting the criminally responsible old elites was worth it for a doomed but carthatic 'progressive' republic and 'stability'.

The SocDems with their statism, cold war apologists for 'enemy's enemy' foreign policy and Socialist Decentism are cut from much the same cloth. It does indeed stink of Burkean call for stasis. That is not to say that there was no need for state intervention, for confronting the totalitarian Soviet regime nor that Afghan women should be allowed to learn to read. Rather, the universal implication of these demands are curtailed by stability, by the seemly immutable rules, norms and lazy assumptions of actual existing 'Liberal Democracy'. This spinelessness makes, by sins of silence, tacit complicity and commission, Ebertism a bloody creed.

However, nothing in comparison to that of the Vanguardists, those thrilled by the actual means of revolution, the Necheavean iconoclasm, the laying bare. Even without having to risk a finger tip, one can be the despoiler of worlds. Vanguardism is the beast that any Socialism must confront, expose and expel. It is the deadliest creedo of the last century. Vanguardism is a derrangement brought on by the enruptions of 1914 onwards, not one that is alien to socialism, but one that is potential.

Whilst vanguardism per se is pretty much dead, its progeny are very much still with us. Fellow travelling 2.0 or 'anti-imperialism' as the far left would call it (I have yet to find what they actually mean) is now stock in trade with much of the wider left. Whilst the Neo-Ebertists assume the infallibility of the good and gracious native state actor, the a-is assume the heroic and essentially progressive nature of any enemy of same state.

The oddity is that both are for the same things and both are aginst the same things in theory. Dickie Seymour is against structured Misogyny and male domination...except in cases where capitalist running dogs might be against it, then it becomes an excusable cultural oddity, to be tidied away post revolution. Brett is all for Unions, as long as they don't delay the Chrimbo post, then they must be smashed as derranged nests of Bolshie insects. They must set aside, deny and ridicule evidence and facts counter to their world view, and especially evidence and facts that might bring them into convergence with the other tendancy.

With pro-war pre-war decents, you detech a similar lack of ease. If you have committed yourself to a venture, with your whole heart, balls-to-the-wall devotion and the people responsible balls it up, you would be fucking livid. Yet, it's all 'mistakes', 'unfortunate', 'unforeseeable', 'impossible to predict'. Its like apologising for the twat who shat in your birthday cake. If I had been pro-war pre-war, I would be in the streets demanding politicians on lampposts. Yet nothing.

The horrific thing is that both sides of the schism see both their own faults, their own compromises and their own ideals in the other

b

@ Bob:

1.

I've already discussed Chomsky-The-Capitalist (in some detail) and Chomsky-The-Chavista (in a little less detail) on my blog. As far as I can see, Peter Schweizer's article denouncing Chomsky for the crime of hypocrisy is quite weak, being both illogical and based, seemingly, on a range of erroneous claims. As for the second -- Chomsky as Venezuelan court jester -- Octavio Alberola's argument is not a whole lot better than Schweizer's.

2.

The issue of 'Chomsky on Cambodia' was canvassed by Christopher Hitchens 25 years ago. I'm not aware of anything having changed substantially on the matter since then.

3.

Not having read Bérubé's book, I dunno what may be said of it inre Chomsky (or the wisdom of pitting Chomsky against Stuart Hall). The distinction Bérubé apparently draws between the 'Manichean left' and the 'democratic left' doesn't seem to me to be terribly helpful, however, especially as Bérubé also apparently seeks to realise a form of 'capitalism with a human face' rather than, say, socialism.

@ Waterloo Sunset:

1.

On the subject of defining Chomsky's political perspective, yes, he often invokes the terms 'anarchist' or 'libertarian socialist', usually in a manner somewhat distant. That is, Chomsky appears to be somewhat uncomfortable providing a precise political self-categorisation. I think this is for several reasons. One is that he views himself as more of an intellectual than as an activist or an organiser -- the implication being that activists and organisers are better placed to engage in such self-identifications. Secondly, because the bulk of his work is not aimed at explicating a political philosophy, or advancing an 'anarchist' position on some subject, but critically examining US and global politics, the meaning and significance of (especially US) state policy, and its impacts upon diverse subject populations.

2.

Regarding Chomsky's liberalism, he's written and spoken on this subject -- that is, his understanding of the historical evolution of liberal thought -- on a number of occasions. Generally, Chomsky places himself, on at least some level, in this tradition. But he also argues, crucially, that many elements of classical liberalism contain within them an incipient critique of an emergent capitalism. Further, that, insofar as liberalism contains within it a commitment (derived from the Enlightenment) to some notion of human freedom, it is assimilable, in some fashion, to later, more open, and more frequently socialist-inspired critiques of capitalism. As I understand it, the key figure for Chomsky in this critical, liberal tradition is Wilhelm von Humboldt, someone whom Chomsky argues represents a kind of transitional figure, one whose political and social criticisms are in accord with a later libertarian (as opposed to liberal) socialism. A version of this argument may also be found in other anarchist writings, including some of Rudolf Rocker's (as Bob notes, another figure whom Chomsky often cites approvingly).

3.

On the shortcomings of Chomsky's 'anti-imperialism': I think this argument bears a number of similarities to those regarding his supposed 'anti-Americanism'. One person to accuse Chomsky of embodying an irrational form of 'anti-Americanism' in his political work is US writer Leonard Zeskind; I've replied to some of his claims on my blog.

4.

Finally, if the closeness of the relationship between an academic (or intellectual, or scholar) and his/her audience is some kind of gauge as to his/her political utility to social movements, I'd argue that Chomsky is incredibly valuable.

More blah later maybe.

I'm sure also someone will explain away Chomsky's conduct concerning Faurisson?

Maybe later on they could explain away why Chomsky agrees with an armed-militia keeping its guns?

Oh, that militia isn't close to home, as that will probably be unforgivable, but its in Lebanon, its called Hezbollah and Chomsky was full of praise for them on his visit in 2006.

As for the political label, I think Chomsky finds it convenient to leave the degree of ambiguity, which gives him coverage when attacked from the right, and most people on the Left are simply bemused, if they can be bothered to think about it is all.

A happy New Year to the Bob and the Denizens of this political watering hole:)

One rule in their own backyards and another faraway.

Equally, I suspect that such people who would normally oppose gun ownership or its mass proliferation in Western countries seem happy for gun ownership, mortars and missiles to be in abundance as long as they are far away from them, and preferably in the Middle East.

Those striking contradictions are so indicative of the Chomskyeques mindset.

Such thinking is hardly an intellectual powerhouse of astute political observations, if universal standards cannot be applied across the world.

5. On far left versus liberal left. It seems to me that many of the pathologies and failures of the left cut across the older extremist-centrist continuum. On many issues, the most important divide is a very different one: between the left that opposes all forms of tyranny and the left that understands the world in terms of Amerika&IsraelBad.

Indecency, for want of a better term, stretches from the Stalinists at the Morning Star through the weird Maoists of ANSWER through unorthodox Trots of the British SWP through Labour leftists like Ken Livingstone through Greens like Cynthia McK to Liberal Democrats like Baroness Tonge.

On the other hand, the people who have got it broadly right on Iran are quite diverse ideologically, and include people close to the Iranian left, many of whom have a rather authoritarian idea of socialism, as well as neoconservatives, Decents and anarchists.

OK. I’ll read SocialRepublican, @ndy and others now.

[Iran has] completely blown the argument that an oppressed people can't make their own liberation out of the water. If their prefered tactic of western military action had been taken this would never have happened.

I don't think the Decents actually argue that an oppressed people can't make their own liberation, do they? The Euston Manifesto, Norm, Nick Cohen, Hitchens, even Harry's Place, don't say this do they? Military action is not their preferred option. It's simply, for some but not all of them, more desirable (or less undesirable) than allowing terrible oppression to continue.

8. On Ebertists versus Necheaveans. Nice comment. This analysis works well for me. However, it is important to keep alive the memory of other traditions. For example, the anarchists and libertarian socialists were excluded from the Second International by the ancestors of the Ebertists and Necheaveans, despite the support of Keir Hardie. Keir Hardie's ILP had a decent record during WWI, and along with its kin "centrist" parties of the so-called Two and a Half and Three and a Half Internationals built democratic mass parties that avoided the flaws of the Ebertists and Necheaveans. Rosa Luxembrg and some strands of the left communist tradition also represent another alternative. These are among the traditions we can learn from if we want any kind of reconfigured radical movement today.

@ ModernityBlog:

On Chomsky's "sucking up to Hezbollah". I've watched the vid (dated May, 2006) to which you provided a link. In it, Chomsky is asked "Do you consider Hizbullah to be a terrorist organization?". He replies that the US does, but notes that the term is used by the 'great powers' in a cynical fashion "to refer to forms of violence of which they disapprove".

Chomsky's "idiocy on Hamas" is apparently based on the notion that, on the one hand, he expresses (in the same i/view) radical opposition to the organisation's policies, while on the other hand, he views Hamas's policy on the Israel/Palestine conflict as being "more forthcoming and more conducive to a peaceful settlement than those of the United States or Israel", for reasons which he then elaborates upon.

He may be wrong, but I'm not convinced that he's an idiot for advancing these arguments. In any case, I'm not sure I understand your following comment on militias, but it appears that you're (again) accusing Chomsky of hypocrisy for being "full of praise" for Hezbollah/Hizbullah, on the one hand, and on the other hand for failing to voice his (apparent) opposition to right-wing militias in the US. Feel free to elaborate.

6.

Finally, and more generally, the distinction Bérubé makes b/w the Manichean and the democratic left immediately brought to mind Ken Knabb's writing on 'Avoiding false choices and elucidating real ones':

http://bopsecrets.org/PS/joyrev2.htm#Avoiding%20false%20choices%20and%20eluccidating%20real%20ones

That's the point eh? Chomksy ducks difficult questions and tries to fudge issues when he's in a corner, rather than say, as most of us would "I am not sure" or something similar.

But hell yeah, why not have more and more guns, more rockets more mortars more fecking rockets that's a really smart idea, if you don't like people, want war and think politics **should** be carried out at the end of a gun.***

As I said, he wouldn't argue that particular line in Western countries, but is happy for it to happen far away.

However, that requires a certain intellectual blindness, he probably thinks that gun control is good in America, for all the obvious reasons, then why isn't it appropriate in other parts of the world, from a socialist anarchist-prospective?

Of course if you’re not interested in real people, or care about if they are blown apart, then Chomsky’s line of the proliferation of missiles guns and weaponry may make some sense, but it isn’t really politics, as you can’t discuss political issues with people after they’ve been blown apart.

And if someone is truly for a better society, then the proliferation of weapons and guns is an issue, not that Chomsky with all of his intellectual might could even grasp that point, as it doesn’t affect him at home.

--

*** sarcasm

@ ModernityBlog:

1.

I don't agree that Chomsky is particularly inclined to avoid difficult questions. On the contrary, in my view, he appears to be prepared to defend views that are otherwise seemingly quite unpopular, and to do so at length. This takes the form not only of his many publications, and thousands of speaking engagements, but voluminous correspondence, with thousands of individuals, on all manner of subjects, over the course of many decades.

2.

Inre the interview w LBC TV: Chomsky (and his wife Carol) visited Lebanon in May 2006. See Assaf Kfoury, one of the organisers of their tour:

http://www.chomsky.info/onchomsky/20060712.htm

Of most relevance in the current context:

"May 11, Hizbullah headquarters, Beirut. We meet Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, the head of Hizbullah, in a heavily fortified compound...

Nasrallah covers a wide range of issues in his presentation, including the arms of Hizbullah, which the US and its allies have demanded be relinquished. Nasrallah presents the issue of the arms in the context of a strategy to defend southern Lebanon which, he argues, concerns all Lebanese and not only Hizbullah. After the meeting, to the pack of journalists and TV crews waiting outside, Noam declares: "I think Nasrallah has a reasoned and persuasive argument that the arms should be in the hands of Hizbullah as a deterrent to potential aggression, and there are plenty of background reasons for that..." Enough to feed the right-wing rumor mill for a long time to come."

So it seems to me that the relevant questions here are: does (or did) Nasrallah in fact have a reasoned and persuasive argument that arms should be in the hands of Hizbullah as a deterrent to potential aggression; what are the background reasons Chomsky claims are of relevance to this argument?

On gun control in the US: presumably, Chomsky has some position on the subject, but his fame -- or infamy -- derives from his views on other subjects. chomsky.info has what I believe to be the most comprehensive online collection of his writings, speeches and so on; the term 'gun control' appears three times, once in an essay by Edward S. Herman, and twice in interviews with Chomsky:

http://www.chomsky.info/interviews/20051223.htm

http://www.chomsky.info/interviews/20031209.htm

Obviously, not a great deal to go on -- if there are other sources, I'm happy to read them.

In any case, I think that what you're referring to is a commonplace criticism, not of Chomsky, but of the 'left' in general -- especially in its ostensibly 'revolutionary' formations -- in relation to the question of 'violence', and that is the apparent preparedness of many to justify or even celebrate violent acts by the 'oppressed', but only, or especially, when these take place in far-away locations (thus excluding these 'cheerleaders' from being in the position of being either victim or executioner -- cf. Camus: http://www.ppu.org.uk/e_publications/camus.html).

4.

In relation to Chomsky specifically, while you've obviously succeeded in this endeavour, I've not. That is, I've not detected any especially glaring failure on his part. Rather, on the question of violence, Chomsky seems to take a position fairly close to pacifism, albeit a form of 'revolutionary' pacifism. (This is especially the case in his writings on the subject of the war in/on Vietnam, and dating from that period). On this matter, Chomsky appears to have been most influenced by the ideas of AJ Muste, whose contributions to the pacifist tradition Chomsky examines in the essay 'On the Backgrounds of the Pacific War' (Liberation, September-October, 1967; also included in American Power and the New Mandarins: http://www.chomsky.info/articles/196709--.htm).

Beyond this, I'm happy to be corrected, but believe that your argument would be more convincing if you were able to cite those instances in which Chomsky has expressed the views you attribute to him (his advocacy of there being "more and more guns, more rockets more mortars" etc). As it stands, I've read most of his major texts, read or listened to a number of his interviews, seen him speak twice, and do not detect the failings that you do. On the contrary, on the subject of violence, it seems to me that Chomsky makes his moral opposition quite clear, and has done on a number of occasions. Further, rather than focus upon his views on the relative merits of Hizbullah/Hezbollah or Hamas, I think a more interesting, and perhaps relevant case -- insofar as Chomsky may be considered an 'anarchist' -- would be his views on, say, the use of violence in the Spanish Civil War/Revolution, in which anarchists were, in fact, violent protagonists.

Finally, on a number of occasions, Chomsky has made it clear that he believes that he does, in fact, speak from a position of relative privilege -- that of a US academic. As an intellectual, Chomsky acknowledges that he has certain skills. These are not the construction, procurement, use or maintenance of small arms, but the ability to conduct critical analysis. As he has also made clear, he believes that, being situated in the US, a principal concern is, and should be, the application of these skills to the deployment of US power. On this point...

===

David Frum (journalist on "Ideas" CBC radio, Canada): You say that what the media do is to ignore certain kinds of atrocities that are committed by us and our friends, and to play up enormously atrocities that are committed by them and our enemies. And you posit that there is a test of integrity and moral honesty which is to have a kind of equality of treatment of corpses in that every dead person should in principle be equal with every other dead person.

Chomsky: That's not what I say at all. In fact, what I say is the opposite. What I say is that we should be responsible for our own actions primarily.

David Frum (journalist on "Ideas" CBC radio, Canada): Because your method is not only to ignore the corpses by "them" but also to ignore the corpses created by neither side, but which are irrelevant to your ideological agenda.

Chomsky: That's totally untrue.

David Frum (journalist on "Ideas" CBC radio, Canada): Well, let me give you an example. One of your own causes that you take very seriously is the cause of the Palestinians. And a Palestinian corpse weighs very heavily on your conscience. And yet, a Kurkish corpse does not.

Chomsky: That's not true at all. I've been involved in Kurdish support groups for years...

http://dgmoen.net/video_trans/016.html [cont.]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7EtB4ai8v8 [2:25]

Forgive me, I wasn't perfectly clear in what I meant, when I said Chomsky ducks issues.

I should have said, Chomsky has a habit of waffling on, avoiding the logical application of his arguments elsewhere and doesn't always make his points as clear as they could be, or at least that's what I found from reading him. It seems to me that there are a lot of hidden assumptions in his arguments, and many of them don’t stand up to scrutiny (Faurisson is one example)

The issue of Hezbollah is fairly simple.

If you oppose guns and their proliferation in your own country, for the reasons that we all know: increased murder rate, knock-on effect on society, brutalisation of people, a trade in a comparably useless product (guns), etc

All the reasons that sociologists point out, massive gun ownership is a social problem and when money is diverted to guns and armaments there is less for the social programmes, etc.

All of these arguments are many and more are fairly common, in the West.

I can't see how anyone who disagrees with gun ownership and its proliferation in Western countries, could, in all conscience, argue for it in other countries.

But that's what Chomsky did, indirectly.

I don't think that there should be masses of guns in Lebanon, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, the United States, Britain, France, Finland or Timbuktu, they are socially divisive and extremely problematic.

Again, it is hard to be consistent and logical if you accept that they should be gun control in Western countries but not in the Middle East.

If, however, you think that gun ownership is a marvellous thing and you can't have enough guns, ever, then it would be consistent to argue for more armaments in Lebanon, but I suspect that Chomsky doesn't hold that position, particularly when it is close to home.

Again, if Chomsky believes that gun control is a fabulous proposition in America and that there should be no restrictions and an increased usage of them, then it would be consistent for him to argue that arming a rightwing militia, Hizbollah, is appropriate. If Chomsky doesn’t believe in the proliferation of guns in the West then why argue that it is appropriate in Lebanon?

PS: I can’t see how someone can be a pacifist or near pacifist when they think that arming Hizbollah is a good thing, bearing in mind the legacy of the Lebanese civil war.

Pacifism and rearmament don’t go hand-in-hand. Do they?

1. On Chomsky the capitalist and the Chavista. The refutation you publish of Schweizer’s allegations is pretty strong. I also agree it is slightly besides the point. If Chomsky is worth taking on, his ideas are worth taking on, not his retirement plan. I do think, though, that there is a sense in which he has become a brand, a celebrity, in an unhealthy way. This isn’t his fault; it’s the fault of his acolytes, many of his are unpleasantly reverential about him. On Alberola’s criticisms, I need to read them more carefully before commenting again.

I expanded on these points at length in my argument with Gabriel Ash, which I extract from here:

I don't accuse Chmsky, Kurlantzick or anyone else from "excusing" Khmer Rouge crimes. I do accuse Chomsky (and, in that one sentence) of minimising and relativising the Khmer Rouge crimes and of other crimes perpetrated by non-Western states, including the Serbs. I cannot provide "chapter and verse" on Chomsky saying the Serbs and the Khmer Rouge are morally exempt of responsibility, because he does not say that, and I don't claim he did. However, I can provide chapter and verse for him minimising and relativising such crimes. On Cambodia, a simple glance at one of his most well-known books, Manufacturing Consent, is enough: description of the actual genocide as just Phase 2 of a genocidal period, with Phase 1 being the US bombings, a claim that numbers of Khmer Rouge victims have been inflated far beyond their actual number. In Manufacturing Consent, he uses a comparative framework, placing Cambodia and East Timor alongside each other in a perverse moral calculus that reduces the singularity of each awful event to an arithmetic game. This comparative approach returns in his comments on Bosnia, linked to in the Hoare piece I link to: "the crimes in East Timor at the same time. These crimes were far worse than anything reported in Kosovo prior to the NATO bombing, and had a background far more grotesque than anything claimed in the Balkans." This, in my view, is simply not true, but it is the logic of comparison that is morally questionable whether it is true or not. I am not saying that we should not compare crimes, but Chomsky's method, framed by a manichean worldview, is to systematically attempt to show that some crimes are overrated and other crimes are underrated, and this is surely a form of relativising and minimising away the non-Western crimes. [...]

It’s not just about the numbers, altho numbers are important. Chomsky likes to play with numbers, claiming that more people died in East Timor than in Kosovo, for example. My understanding is that around 1.7 million died under Pol Pot out of a population of around 7 million, and that the deaths were basically deliberate. Many were killed by hand (100s of 1000s, if not over a million), while others were starved because they were considered sub-human (the slogan was "To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss"). A summary of different estimates is here: http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat2.htm#Cambodia. This is a genocide, and should be tried as such. [...]

Calling the US bombings Phase 1 of a genocide is inaccurate, because the bombings were something else. This is like calling the Allied revenge on Germany after 1918 “Phase 1” of the Holocaust. Calling it “Phase 1” is not “telling the story”; it is obscuring the story. Each crime was singular, and to blur them together insults the victims of both.

1. On Chomsky as anarchist or not, again. On one level, I think Chomsky is admirable in not seeking to set out any total Chomskyan political philosophy, but rather focusing on “critically examining US and global politics” etc. It doesn’t matter whether he is or isn’t an anarchist. Why it does, though, kind of matter a bit is that Chomsky is a key figure in what I think of as the ZLeft, the milieu around ZMag, MRZine, CounterPunch, Common Dreams and so on: a left that takes on the rhetoric of anarchism and rebellion but ends up supporting authoritarian and totalitarian regimes and movements around the world. Chomsky’s “anarchist” aura lends libertarian credibility to this milieu, which is why the question of whether or not he is Chavez’s court jester is important.

Now I'll read the more recent comments!

1. On AJ Muste, see this http://poumista.wordpress.com/2009/11/30/my-obsessions/#comments scroll down to third comment, by M Ezra. (On Muste: "This is the man who said in 1940, “If I can’t love Hitler, I can’t love at all.”")

2. On militias and guns. Chomsky's associate Alexander Cockburn supports both. See third item here: http://brockley.blogspot.com/2008/06/wednesday-miscellany-law-and-disorder.html

Regarding The Beatification of St Noam: yeah. On the one hand, he's treated as being a celeb by some; on the other hand, SFW. From my perspective, his ideas should be treated in the same manner as anyone else's: analysis, understanding, and criticism. Otherwise, what's the point? (I mean, I could riff on the nature of alienation under capitalism, and the fact that 'expropriating the expropriators' has an intellectual and cultural dimension to it, but fuck.)

On Chomsky and Cambodia, a few things. To begin with, 'Manufacturing Consent' was written by Edward S. Herman and Chomsky. A minor point, perhaps, but one often overlooked. Secondly, yes, the authors distinguish three 'phases' in the 1970s, "the decade of the genocide" (a phrase taken from the title of the Finnish Inquiry Commission report). Phase I of the "decade" is dated from 1969 through to April 1975; Phase II April 1975--December 1978; Phase III the remainder of the period in question.

On the scale of the genocide committed by the Khmer Rouge, I don't believe it's accurate to state that Chomsky (and Herman) simply claim that the number of the regime's victims has been exaggerated; rather, they claim that accurate reporting was subordinated to other interests. (In which context, it's worth remarking that the comparative analysis of the genocides in Cambodia and East Timor which appears in 'Manufacturing Consent' was preceded by a previous volume by Herman and Chomsky -- 'The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism' (1980) -- in which the matter is also discussed.) That is, I don't agree that, in examining the media response to atrocities in Cambodia and East Timor, Herman and Chomsky employ "a perverse moral calculus that reduces the singularity of each awful event to an arithmetic game". Rather, their principal concern -- at least in 'Manufacturing Consent' -- is to examine how their 'propaganda model' functions in this case. Or to put it another way, their work "systematically attempt[s] to show that some crimes are overrated and other crimes are underrated", and that such treatment may be understood by way of examining the political economy of the mass media.

More generally, on numbers, I'm unable to comment on Chomsky's remarks concerning East Timor versus Kosovo; on casualties under Pol Pot, in 'Manufacturing Consent', Herman and Chomsky cite the Finnish Inquiry Commission, which estimates that somewhere between 75,000 and 150,000 people were executed outright during 'Phase II', while another million died as a result of killings, hunger, disease and overwork. They also cite Michael Vickery, who estimates that 750,000 died, 200--300,000 of whom were executed. More detailed discussion is of course included in both 'Manufacturing Consent' and 'The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism'.

Finally, while it may be worthwhile, or useful, to distinguish Phase I from Phase II, as I understand it, Herman and Chomsky's periodisation is based on 'Kampuchea: Decade of the Genocide, Report of a Finnish Inquiry Commission'. Regarding Phase I, I'm not sure how the bombings can or should be described in your view: the same Commission estimates that 600,000 died during Phase I, while 2,000,000 became refugees. In any case: i) the relationship between Phases I, II and III are explicated in the relevant chapter of Herman and Chomsky's book; ii) I'm not convinced that the analogy you make -- between the effects of the Versailles Treaty on Germany and the Holocaust/Shoah, on the one hand, and the US bombing of Cambodia and the Pol Pot regime's crimes, on the other hand -- is apt, or accurately represents their argument, which is less concerned with historical causation than it is media reception.

ZMag / MRZine / CounterPunch / Common Dreams: a 'Praxis of Evil' eh? Hmmm, maybe. AFAIK, MRZine, CounterPunch and Common Dreams, while occasionally including some references to it, are not anarchist publications; nor, for that matter, is ZMag (tho' it may have a little more, explicitly anarchist, content). Do these publications support authoritarianism? Not explicitly, no. But then, there are few who do. Does Chomsky's publication by these sources help to provide them with an "anarchist" aura? Maybe. But the label is not a warranty, and the proof is in the pudding.

Now, where's that bloody omelette?

Sorry, maybe I missed it but what is Chomsky's view of the Militia in the US,is he in favour of them? and is he for gun control in the US, or not?

And they frequently support regimes which I strongly consider to be authoritarian, including Iran's, Cuba's, Venezuela's. Che features on the front page of Common Dreams today. CounterPunch is complaining about "the Israel Lobby" and its war on Hezbollah's TV station, Al Manar (Hezbollah being, in my view, fascist). It has lots to say on US aggression towards Iran and the US's imagining of Iranian nuclear capabilities, but has nothing critical of the Iranian regime anywhere in the articles on its front page now, despite the revolution and repression going on there. (It also continues to publish the vile Gilad Atzmon, but that's another issue.) MRZine, more offensively, publishes several defences of the Iranian regime, including one from Hugo Chavez. ZMag has nothing offensive on its front page, but has published no support for the Iranian uprising since October, and meanwhile lots of criticisms of America's toughness towards Iran. It also has a considerable amount of pro-Chavez material and nothing critical in the last months.

Chomsky and Herman (C&H) contrast Ponchaud to Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution, by George Hildebrand and Gareth Porter, a defence of the Khmer Rouge which claims that mass starvation was a "myth". Sample sentence: "The evacuation of Phnom Penh undoubtedly saved the lives of many thousands of Cambodians... what was portrayed as a destructive, backward-looking policy motivated by doctrinaire hatred was actually a rationally conceived strategy for dealing with the urgent problems that faced postwar Cambodia." C&H praise this book. They also argue that Ponchaud heavily overemphasises victim numbers and claim that this overemphasis is a common feature of Western reportage. They do not make a comparison yet to East Timor, but simply call for extreme skepticism about claims that large numbers of people were dying in Cambodia.

C&H next published After the Cataclysm: Postwar Indochina and the Reconstruction of Imperial Ideology (1979). Here again, even as Ponchaud's account was being tragically vindicated by the evidence that was unearthed after the Vietnamese liberation, C&H argue for low numbers. They further argue: ""The ferocious U.S. attack on Indochina left the countries [of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia] devastated, facing almost insuperable problems. The agricultural systems of these peasant societies were seriously damaged or destroyed... With the economies in ruins, the foreign aid that kept much of the population alive terminated, and the artificial colonial implantations no longer functioning, it was a condition of survival to turn (or return) the populations to productive work. The victors in Cambodia undertook drastic and often brutal measures to accomplish this task, simply forcing the urban population into the countryside where they were compelled to live the lives of poor peasants, now organized in a decentralized system of communes. At heavy cost, these measures appear to have overcome the dire and destructive consequences of the U.S. war by 1978." This, it seems to me, is obscene.

C&H were by no means unusual on the left for taking this sort of line in 1979. However, as the 1980s went on, the evidence of the genocide built up, and many people changed their mind. C&H stopped describing the Khmer Rouge takeover as "liberation" and stopped claiming that the regime was actually a good one. By 1988, when they wrote Manufacturing, they had accepted that the regime was indeed genocidal, but they continued to claim that the numbers reported in the West were exaggerations; no one can know the true numbers they say. Crucially, they also intensified their contention that the US bombings were the real cause of the Khmer Rouge genocide. They do not mention Chinese support for the Khmer Rouge.

Since 1988, the evidence has continued to build up, and the figure of 1.5 to 1.7 million excess deaths is now accepted by every expert, with many saying that this is a conservative estimate. Yet C&H continue to talk about Michael Vickery's estimate (made in the early 1980s) of 750,000 as plausible. The fact is that no one reputable other than C&H any longer ever gives a figure of below a million as the lower end of the range, yet they still do.

C&H also continue to make a big deal out of a CIA report that made an early and very low estimate of deaths. When they turn to this, they describe its figures as "ludicrously" low, which they add to their evidence of Western distortions. However, the Finnish Inquiry which they rely on heavily gives almost identical estimates, which they don't criticise. The latter was published in 1984, and significant evidence has emerged since then.

Their claims, in 1977, in 1979, in 1988 and subsequently go far beyond using Cambodia as a case study for their media model. Their claims are also about responsibility for genocide, and scale of genocide. However, their calculus of comparison and their comparative methodology is dodgy, because it mirrors the systematic bias they claim to uncover: they systematically minimise non-Western atrocities and systematically exaggerate Western ones.

Finally, just to note that I see the US bombings that preceded the Pol Pot regime and the US support for the regime as terrible, terrible crimes, and I in no way want to minimise them in putting all this effort into disagreeing with C&H.

Incidentally, the Hitchens defence of Chomsky is here: http://www.chomsky.info/onchomsky/1985----.htm

A systematic criticism of that is here: http://www.mekong.net/cambodia/hitchens.htm

To take comments in turn:

Matt-

Thanks for that. I'll definitely order this from the library when I get the chance. I do fully understand the issues with critqueing a book I've only read summaries of, but I suspect a lot of people in this discussion are in that situation.

And he certainly does describe what he means by the Manichean Left. A reason for the term is that he doesn't want to concede ground to those who think they're "leftier." For some, it can work out that to declare the sky to be blue is to declare your allegiance to mainstream, bourgeois values. To rebuke them as "far leftists" or in a variety of other ways doesn't work because they take that as a compliment.

Oh, it's basically a perjorative? In which case, that's fair enough. I'd be utterly hypocritical to take issue with it on that ground, though personally I still prefer the term "cobweb left" (cobs for short) as it requires less explanation. The only issue I think remains with that, in that case, is the old issue of whether it's wise to use language that will exclude a lot of people from understanding your meaning. The 'man in the pub' argument.

At the same time, he doesn't want to get into claiming the authority to declare a proper way to be a leftist, because that's a useless argument that diverts discussion from what's correct to what's left.

That strikes me as something of a copout. Obviously, not everything that is left is correct nor is everything that is right incorrect. I'd certainly consider Stalin a leftist (in fact I consider Stalin under Russia to be socialist, not state capitalist). But labels like "left" and "right" have a meaning, certainly in popular usage. To abandon that argument in favour of simply arguing that we should argue for what is "correct" is even more vague. Everybody would consider their own political views to be broadly correct, from fascists to liberals to anarchists. This strikes me as a convienent way for people who no longer hold views that can be described as meaningfully leftwing to hold on to the term for emotional reasons and/or so they can still claim the legacy of people like Orwell.

1. I'm not sure that it's fair to criticise Chomsky for lack of nuance and simplistic analysis with the reporting of his views. That's the nature of both celebrity and the mass media. Something needed in the recomposition process is for a lot of people to get over the fear of 'populism'. We need our ideas and arguments to be accessible and interesting. Early Class War were actually pretty good at this, though they're mostly a self caricature now.

2. On what grounds do you criticise Chomsky then? I'm pretty sure he'd consider Pol Pot a "lesser evil" than America in the debate, not a force for good. Obviously you can argue with that. But I don't think you can consistently argue that support for reactionary groupings for tactical reasons is always a bad thing, when you've accepted the "lesser evil" premise that leads to that conclusion.

3. Oh, god, Rocker. I'm not a fan, as you can imagine. He was also an obvious influence on the Freedom crowd, though they've got a lot less shit recently.

4. I think that's a massive oversimplification of the anti-imp position. Largely, I don't think the likes of the SWP see the Iraqi 'resistance' as good, per se. It's that they see it as a lesser evil compared to US power, particuarly when the US is undoubtably the only remaining superpower in the world. I think that's more accurate, but I also think it's a lot more difficult for you to take issue with for the reasons I outlined in point 2.

7 (or 6!). The hypocrisy is my main point. And the comparison between the two illustrates that liberation from oppression is not their goal. In fact you illustrate that yourself:

The Decents would respond, presumably, that Greece and Iran are very different because Greece, while corrupt, is a liberal democracy with freedom of speech."

A thought experiment. Replace Decents with "Stalinists". Greece with "America" and Iran with "Russia". And "liberal democracy..." with " a worker's state".

The Decents are authoritarian through and through. And they aren't allies for anybody who believes in pro working class politics.

And I think realistically military invasion is their prefered option, Iraq is what started the whole Decent movement in the first place. And by supporting military action, they are in effect saying that they don't believe that a people can make their own liberation.

To be clear though, I don't think that everyone from a left background who supported the invasion of Iraq is a Decent, though I do disagee with them. It's not the litmus test for me it is for a lot of people on both sides of the debate.

I'd say the main traits of the Decents are

a) broad support for Western foreign policy, particuarly when it comes to military operations.

b) an abandonment of socialism in favour of liberalism, a belief that capitalism should be at most reformed, not abolished and a de facto abandoment of class politics.

c) hostility to radical social movements in the West.

d) a willingness to make alliances with conservatives, as they consider domestic social issues to be less important than foreign policy.

So, by that definition Stuart Craft of the IWCA (who was pretty ambivalent about the Iraq War) obviously wouldn't qualify. Neither would the Drink Soaked Trots or Hitchens. Whereas Oliver Kamm or Marko Atilla Hoare certainly would. While not perfect, I think that's a mose useful working definition than seeing it solely in terms of Iraq/Afghanistan.

Excellent post and I agree with the bulk of it. The only thing I'd be iffy about is support for state intervention, as you'd expect.

The part about the Decents and the Anti-Imps being two sides of the same coin is spot on. I'm not sure they're aware of it consciously though. For their self-perception to avoid falling apart, they have to ignore the glaring commonalities between them and their 'enemies'.

1. I also think that Chomsky is reluctant to provide a specific political categorisation for himself because he likes having his cake and eat it. He likes being a celebrity I suspect and for that he needs to appeal to the Democrat voting liberals. Openly supporting the anarchist movement would be a barrier to that. That would fit with his concentration on foreign affairs as opposed to domestic policy- it's actually far less controversial to do that.

2. That's a fair point. It is the case that Chomsky is attracted to the liberal anarchists as well. I'd see him as a signifier of what's wrong with the US anarchist movement. In the same way as Crimethinc. (To be fair, the only reason the UK movement is slightly less stupid is the combination of the miner's strike and the poll tax movement).

3. As I pointed out above, I don't think that Chomsky does concentrate his fire on the US where it comes to domestic issues. And arguing that Chomsky is "anti American" because he concentrates on his own country first is very different than the argument that Chomsky is too weak on reactionary forces opposed to the US.

4. That depends on who you think Chomsky's audience is. I don't see much evidence he is orientated towards the working class, which is the crucial factor for me. I'm not saying that I don't think some of his work on foreign affairs is very valuable. Just that I think he's extremely flawed.

I'm no fan of Hezbollah, but the analogy with the US militias doesn't work. Hezbollah's military wing aren't a private militia anymore. They're formally recognised by the Lebanonese state as an army. That makes them no less or more legitimate then any other state army. To turn your question back on you, do you call for the disarming of every state army or is this specific to Hezbollah?

On your other point, if Chomsky does support gun control, that's a damn fine example of his liberalism.

There is no way gun control should be supported in the context of the US.

Firstly, by doing so you buy into the concept that states should be allowed a monopoly on violence (army, police etc.)

Secondly, all the widespread hostility to guns by the American liberal left has achieved is to make sure that the bulk of the firepower is concentrated in the hands of the right.

Finally, without having guns to defend themselves against police oppression the Black Panthers wouldn't have been able to organise within their community.

The only objection I have to radicals in the UK arming themselves is a tactical one. (It wouldn't be a good idea for us to all start getting hold of illegal firearms for obvious reasons). I have no ideological problems with guns.

When were Hezbollah formalised onto the same level as the Lebanese army, when?

ANSWER was founded by the Workers World Party (WWP), who were actually Trots who split off the (US) Socialist Workers Party, in support of China, during the Sino-Soviet split. (A few years ago the WWP split, the Party for Socialism and Liberation leaving, and apparently the two now share ANSWER.) Although at first glance the heavy anti-imp and focus on "oppressed internal nations" (ie people of color) seems like classic Third World Marxism, their support for trans and queer rights shows that they still retain a (post)-Trotskyist ideological core. So its wrong to say they're Maoists; they are highly idiosyncratic Trots. And highly annoying ones at that.

Chomsky's support for Hezbollah dates from at least May 2006, it could be even earlier.

That's two years before 2008.

So at the time of Chomsky's visit in May 2006 and his vocal support for Hezbollah they were not by the standards of Lebanese politics "legitimised", they were just another rightwing militia.

Chomsky wasn't supporting, even with the most tenuous of reasoning, part of the Lebanese government, he was supporting a rightwing militia and essentially arguing that guns are better than butter.

This is definitely the right room for an argument.

That said, I'll respond to comments by ModernityBlog / Bob / Waterloo Sunset later. Given the detail with which Bob has commented on Chomsky inre Cambodia, however, I may be forced to blog about that subject in particular.

PS. radicalarchives.org looks neat.

PPS. Australia now has its own "Defence League". Huzzah!

http://slackbastard.anarchobase.com/?p=12289

I think the SWP themselves think of the Iraqi “resistance” as a lesser evil than American imperialism (I think they’re wrong) rather than a good in itself. However, the very use of the word “resistance”, whether used honestly or cynically means at the very least they are glorifying this lesser evil, promoting an illusory view of it. Whereas the likes of Galloway actually do think it is glorious.

I think that the more broadly defined Decent movement emerged not in response to Iraq but a bit earlier, after 9/11, with the disgust that many basically decent people on the left felt at the common response from many others on the left (including Chomsky) that this was basically America's chickens coming home to roost. Very few of these people saw military intervention as a preferred option, but many did see it as a less bad option.

On the workers' state/liberal democracy thought experiment: I get the point, but I do think that actual liberal democracy is qualitatively different from Stalinist totalitarianism; they are not just two sides of the same coin.

Of course you're right. 'Libertarian' socialism or Dem soc is a third tread, one that has proven to be far more principled and dedicated to actually confronting inequality and injustice than the 'Ebertists' and the 'Necheaveans'. Even within some of 2I and early post 2I parties, there was a strand of a-statist and rights based thought, the workers' self help groups of the SDP. I would count myself from coming from such a heritage and, unsurprisingly, see it as the starting point for a new socialism, capable of thriving in the future. Alas, we have normally been marginal at the best of times, invisable at others.

WS

If one looks at the pre-1918 calls for socialisation and what would become nationalisation in the early to mid twenties, one can see the difference. The Rate merely asked for legal central sanction for workers control, they did not seek state control or central planning. Nationalisation inevitably, given its wartime inception, might have removed some workplace power from the boss class, but also took much from the workers themselves. While raising up the state as arbiter might, in a roundabout kind of way, given democratic oversight and social consideration to overall management, it was intrisically a co-option. Workers concerns merely joined the classic Liberal internal contest of interests within political systems still partially controlled by methods best used by elites. Socialisation, as invisioned by the much of the pre 1914 left was much more directly democratic and actually attempted to deal with alienation in a practical way. A rare thing.

On Chomsky.

One of the most 'seductive' things about him and his weltanschuung is his seemingly unperturbable grasp of facts. As long as one doesn't look too close at the cackhanded used of evidence and plain deceit, you have the feeling of joining a band of gnostics. Common enough like with dogmatic Marxists or Randians

But it is a static form of hidden knowlegde. The America he so condemns is always the America of the darkest moments of the Cold War, of Jim Crow, and thus America's enemies are always proxies for Arbenz or Allende or MLK. And as Mr Coates points out, such stasis is getting very very boring.

One (very) small redeeming aspect. Chomsky does always encourage to believe in political (tho extra-party) participation amongst his audiences in the west. In and of itself, that is a good thing.

On alliances with conservatives, all of these sharply condemned the Conservative Friends of Israel dalliance with the Polish and Latvian right, which created a minor spat in the Jewish Chronicle between neocon editor Stephen Pollard and decentist political editor Martin Bright.

Sorry, getting a bit angels on a pinhead. I'll stop.

Oh, and Radical Archives is a very cool site, and I forgot to go to Reading The Maps.

On lesser evilism. Chomsky initially thought of Pol Pot quite positively, and spoke of the Khmer Rouge victory as liberation.

Point taken. The only vague defense of that I can think of is that I believe that Chomsky was at least genuine about being utterly wrong.

it seems to me that the sort of suffering that existed under Pol Pot or Hitler was so great that any regime change, even if effected from without by states with bad motivations, was desirable. The prospect of the Cambodia people rising up against Pol Pot was just unthinkable.

Serious question. Do you believe that allying with Stalinists in Spain was the correct thing to do, despite how it turned out? And how do you reconcile that with your oppostion to popular front establishment anti-fascism in the UK?

Besides that, I think we have to look at the wider picture. And lesser evilism has consistently failed to provide a solution to oppression. It's replaced one reactionary regime with another. Iran is a perfect example of what leftist less evilism leads to, where you had the left react to the undoubted evils of the Shah by lining up with the Mullahs. By doing so, weren't they morally culpable for the later atrocities?

I think the SWP themselves think of the Iraqi “resistance” as a lesser evil than American imperialism (I think they’re wrong) rather than a good in itself. However, the very use of the word “resistance”, whether used honestly or cynically means at the very least they are glorifying this lesser evil, promoting an illusory view of it.

It's arguably used cynically, because of the obvious rhetorical similarites with groups like the French resistance. Technically, it's not incorrect though, surely? Purely in linguistic terms, a group resisting any other group is the 'resistance', without that attaching any value judgement to the term.

But how can you possibly argue that the SWP glorify the Iraqi 'resistance' through the use of the term, but describing Russia's victory on the Eastern Front as 'liberation' isn't de facto cheerleading for Stalinism?

Whereas the likes of Galloway actually do think it is glorious.

Absolutely. But Galloway has been grubbing round for a new cause to support since the fall of the Stalinist states, so it's unsurprising.

On Decentism. I guess there is Decentism and there is Decentism (as there is far leftism and far leftism). If we are talking narrowly about, say, some Harry's Place people, then I'd agree with a lot of what you say (I use the term Harryism for this).

Isn't one of the main strands of the pro war left's arguments that you can't be a fellow traveller of groups like Hamas without being tainted by the association? And while Harryism may be a particularly easy target, other more 'moderate' decents still cite them uncriticaly and largely talk about them as being on the same side. Is being a fellow traveller of Harryism actually that much more acceptable then being a Harryist?

It's true that there are people who have disassociated themselves strongly from Harryism, but they're also the same people who have washed their hands of Decentism as well. (The Drink Soaked Trots being the obvious example).

If you are talking about Norman Geras, then some of it seems clearly wrong (can you really say he is authoritarian through and through?).

I have to say I don't actually know enough about Geras to draw any valid conclusions.

Who on the left actually saw 9/11 as justified or even a broadly good thing? (Green Anarchist may have come close. I don't know that for certain, but at the time I recall that they were describing any act of nihilism, from kids smashing up bus shelters to the gas attack in Tokyo, as an indicator of societal breakdown).

Is it really that outrageous to suggest that 9/11 may have at least been influenced by previous events? Do we have to take the 'end of history' approach to every single atrocity? Personally, I see the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as being closely linked to the US funding of Islamic fundamentalist groups in Afghanistan. Is that really beyond the pale?

If, on the other hand, you're defining "Decent" as anyone who saw 9/11 as entirely unjustifiable, without qualifications, that's way too broad. It would even include the likes of Class War.

Very few of these people saw military intervention as a preferred option, but many did see it as a less bad option.

What's the difference between "preferred" and "less bad"?

On the workers' state/liberal democracy thought experiment: I get the point, but I do think that actual liberal democracy is qualitatively different from Stalinist totalitarianism; they are not just two sides of the same coin.

Surely capitalism is responsible for at least as many deaths as Stalinism?

Even if you accept that though, does that justify refusing to support progressive resistance against state power in liberal democracies? Or does it illustrate that, actually, the "Decents" are in effect pro capitalist partisans?

If so, maybe a new term is needed to reflect that.

How about "the White Army"?

http://standpointmag.co.uk/node/2596

On Chomsky in general. I ought to repeat that I do have a lot of respect for him. A lot of his work is very useful. Some of his mistakes are indeed honest.

On "the resistance". Well, yes, purely technically, anyone resisting anything could be "the resistance". In my household, say, I am "the resistance" to domestic chores. But usually when you hear it, you think of the French people in fields at the dead of night blowing up bridges and stuff like that. The "insurrection", in my mind, is a more neutral expression. This, incidentally, has been a fierce topic of discussion at wikipedia, where the stakes are quite clear.

On liberation. I guess you are right about that.

On preferred versus less bad. I think you know what I mean. And I think I'm right. Apart from Hitchens and maybe Kamm, few Decents were actually enthusiastic about the war. See Ian McEwan Saturday for insight into the this.

On Harryism and fellow traveling. I don't get your meaning WS. Fellow travelles are by definition tainted by the association, no? But you only really use that phrase when the thing being associated with is monstrous, as in fascism and Stalinism. Being a fellow traveller of Harry's Place doesn't seem too horrific a crime to me. It may be that they are too quick to call anyone with the most remote link to Hamas a fellow traveller of Hamas, but there is such a thing as a Hamas fellow traveller, and it is unpleasant. Am I missing your point?

On 9/11. I don't think anyone serious on the left saw 9/11 as a good thing. But the "chickens coming home to roost" response was incredibly common. Of course, it was true on one level: the events were related to the sequence of events that preceded it, including American foreign policy. But it fundamentally misinterpreted the nature of Al-Qaeda's millennial ideology, and it explained away the evil of what they did.

One more to come.

I first started thinking in terms of United Front versus Popular Front under the influence of Trotskyists, and especially through the writings of Leon Trotsky. Trotsky developed the ideas in relation to the correct policy of the Communist Party in Germany. He (rightly) criticised Third Period ultra-leftism, whereby the Social Democrats (Ebertists?) were deemed "social fascists" and therefore just as bad a the Nazis. He called for a united front with them, but not an alliance with "bourgeois" anti-Nazis. I followed that line of reasoning.

On Spain, on the other hand, I came to my position a little later, under the influence of anarchists and left communists, and especially through the writings of Orwell. Here, while Franco was the real enemy, the Communists came to be the enemy too, and alliance with them was wrong. I followed that line of reasoning.

Essentially, I realise now, these two positions are contradictory and incompatible. But I don't know how to resolve them. I honestly don't know what course of action I would have taken had I been active in Spain or Germany in the moments in question.

The comparison with Iran is good, because the Shah stands some comparison with Franco (Franco was more culturally repressive than the Shah, if equally politically repressive), and the Iranian revolution, which I am sure I would initially have defended at least to some extent, ushered in something that, it is now very, very clear, was far, far worse. (This makes Chomsky's initial positive appraisal of Pol Pot also more understandable, as an apparent positive step from the Lon Nol military regime.)

Just looking at the Chomsky piece in Standpoint (thanks Flesh) and the Chomsky interview it relates to.

Chomsky's very cagey about his alleged friendship with Chavez, and constantly asks why people obsess with this, when they could equally say it about other Latin American heads of state. The question arises about Chavez, not Lula (who I know a lot better) or Correa (who I just spent a few hours with) or many others who are at the heart of the “pink tide” because Chavez is demonized by state/media propaganda. I don’t accept that.

To me, there is a fundamental difference between Chavez, a deeply authoritarian ruler, and Lula, a fundamentally democratic figure, and Chomsky's question is therefore deeply disingenuous. By "not accepting" media demonization, he is implicitly defending him, which is wrong.

http://slackbastard.anarchobase.com/?p=12441

What about the point concerning arming of right-wing militia

Did the point get made?

Um... I've responded to Bob (at length), and wrote that I would return to yrself and Waterloo. But I think it would help me do so if you could re-state yr argument again inre Chomsky and right-wing miltias in the US. As I understand it, it has something to do with an alleged double-standard: supporting Hamas, on the one hand, but being in favour of gun control in the US, on the other. Please correct me if I'm wrong.